The internet of things

The identifier for the new era of internet interaction was founded on the phrase above. Like "web 2.0" before it, and the "information superhighway" of internet antiquity, those of us keeping tabs on the digital media industry were bludgeoned over the head with this phrase. Did we use it in our new article? Did we make sure to use an 'internet_of_things' keyword at the foot of our latest post? Failing to do so, of course, would mean that our partners in SEO analytics would be sending us another round of notes concerning 'content visibility improvements'. Failing to do so meant that our relevance score according to the BNW-esque World Controllers' offices would leave us off the VIP list in their ever-changing, always mysterious algorithm.

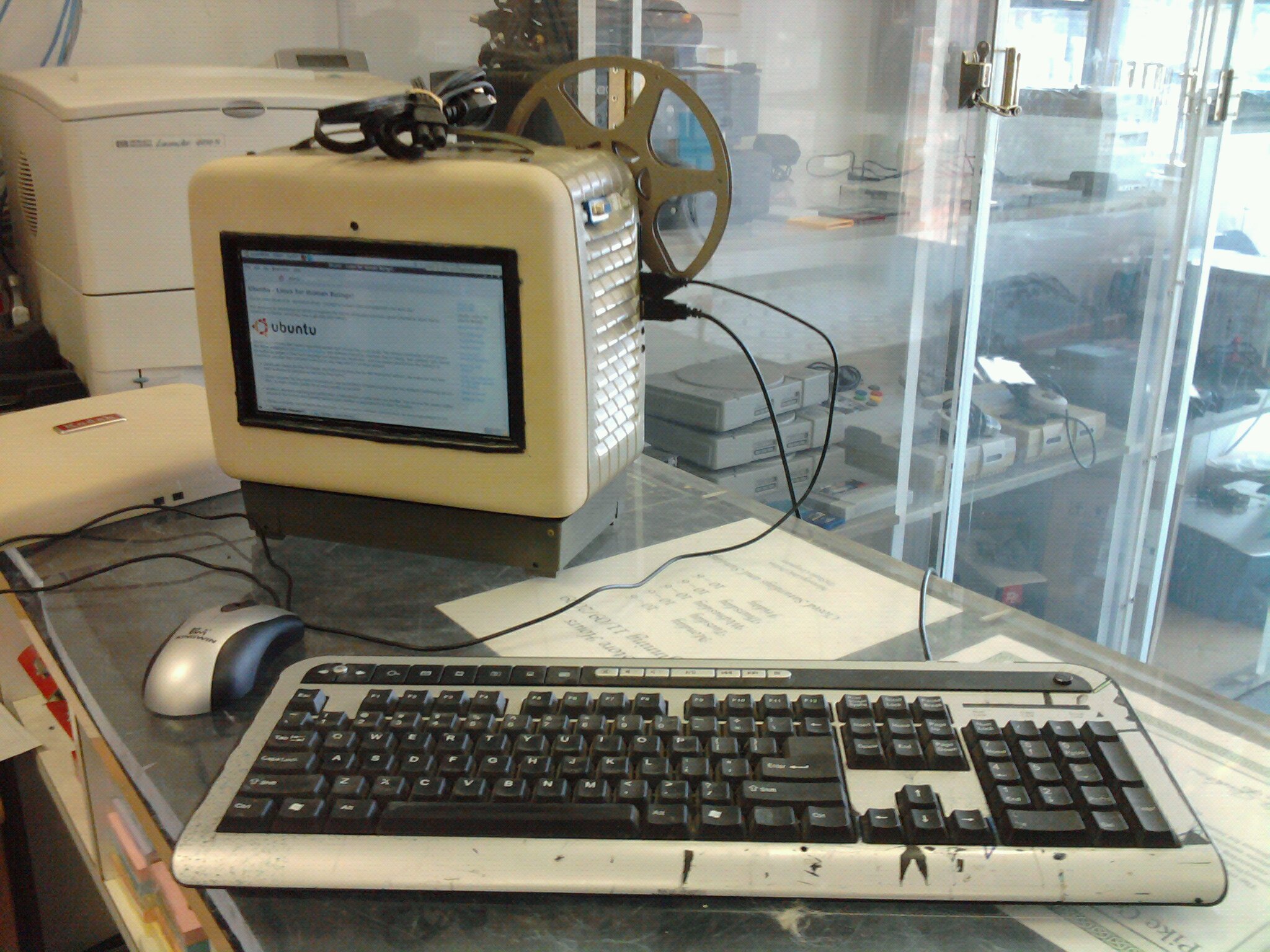

Change and meaningful innovation have always been the red blood cells and plasma of digital media, and we were used to having to tweak our SEO rituals to please the digital spirits...but somewhere between the cleanup & streamlining of Web 2.0 and the "Internet of Things" buzzphrase that came between Web 2.0 and what the digital jetset now calls 'Web3', innovation stopped being defined by a more efficient, user-friendly way to do the job.

Innovation came to mean do it differently, for better or for worse. Sometimes it meant updating an interface to adhere to a trending design standard that made UI less navigable (and thus, left users themselves understandably more upset). Often times it meant changing a familiar layout simply to change it, even if visitation and usage statistics soundly indicated that they were happy with the way it functioned before.

designing disorientation

One of the most astonishing things about modern web design, especially among the major players, is a willingness to trade familiarity for obfuscation in the name of novelty. Social media sites are a prime example where one can find important top-level (i.e. the first or most conspicuous visual option) functionality suddenly buried in overwhelming menu trees or accessible only from a new (and thus, to regular users, obscure) wing of the site.

What used to take one click became three. Something that used to be at the fingertips was now on a menu branch that could only be accessed with an additional pageload. Why? In terms of user experience (UX), why would we move users from the easy, clear grid of Midtown to the wandering Dutch maze of Lower Manhattan?

Utility + FUTurE = futility

The larger a website is, the more recalcitrant it will be to a negative user response to major design or UI changes, no matter how visible. There was a shift sometime in the last decade that led to less streamlined interfaces, and there's a simple, albeit cynical theory in play:

The most lucrative website for a communications company whose primary market values are in user analytics, demographic information, and advertising revenue is NOT a streamlined, easy-to-use site.

Rather, the ideal is to create a maze of pageloads, scrolls and impressions. This not only maximizes advertiser exposure, but it also provides mountains of behavioral and optics-tracking analytics. In a period of competition, balances have to be struck between the saturation practices described above and the patience of the average user. If your site is confusing, people simply won't use it...unless your competition is all bought out or maligned by your media partners, in which case, your users are more likely to stick around, no matter how terribly they might score the UX.

just try to be good

"Don't try to be original, just try to be good. That sounds sort of naive, but it's true."

If you've even flirted with design, this Paul Rand quote might seem as cliché as the dust-coated "Information Superhighway" term was to those of us who remember Prodigy, Compuserve, and GEnie. We've reached a point, though, where it seems as if the same group of design and UI enthusiasts who posted this same quote on their tumblr pages ten years ago have completely forgotten the sentiment it embodies.

The best of the internet's communication services make our lives easier by taking less of our time and focus, not more of them. The best UX is one that doesn't frustrate you. The best UI is one that you can quickly understand. If it has to be updated, the best update choice is the one that dependable daily users would best adapt to.

These ideas seem cliche, too. More obvious than sand in a desert. But if we're not following them as designers, I hope that the reason is something silly and esoteric about art & expression. I would love to believe any excuse rather than the cynical one I've imagined above.